Author: Dave

“Advancing MM 1: Market Maker Inventory Quoting System“

“Advancing MM 2: Market Maker Order Book and Order Flow“

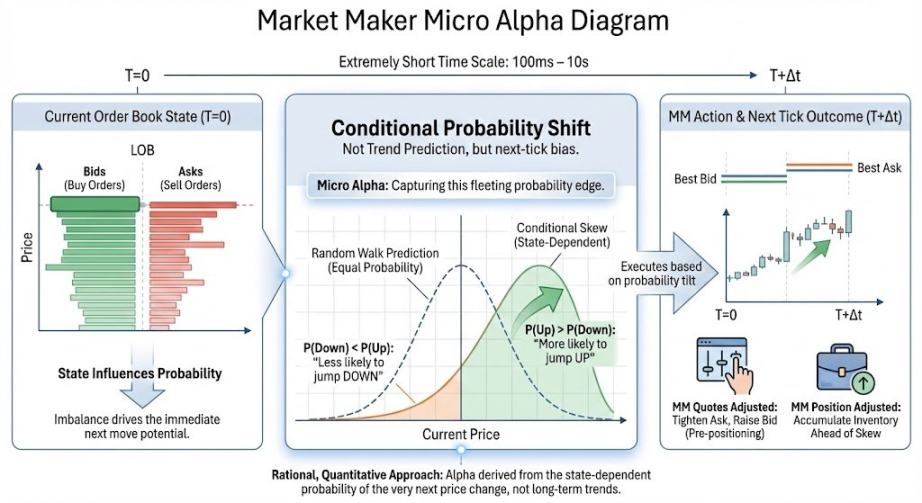

The previous two episodes mentioned order flow and inventory quoting, making it sound like market makers can only adjust passively. But do they have proactive strategies? The answer is yes. Today, we introduce statistical advantages and signal design, which are the “micro alpha” that market makers pursue.

1. Market Maker’s Alpha?

Micro alpha refers to the “conditional probability shift” in the direction of the next price movement / mid-price drift / trade asymmetry over extremely short time scales (~100ms to ~10s). It’s important to note that the alpha in a market maker’s eyes is not about trend prediction or guessing price movements; it only requires a probability shift, which is different from the alpha we commonly refer to. In simpler terms:

Market maker statistical advantage can be understood as whether the order book state “tends” to move the price in a certain direction within an extremely short time window. If a market maker successfully calculates the probability of the next millisecond’s price direction using certain indicators, they can: 1. Be more willing to buy before a likely increase. 2. Quickly withdraw buy orders before a likely decline. 3. Reduce exposure during risky moments.

The financial basis for predicting the next price direction is: due to factors like order flow, order book volume, and order cancellation ratios (to be discussed later), the market is not a “random walk” Brownian motion in a short instant but has directionality. The above statement is the financial translation of the mathematical concept of “conditional probability.”

With this alpha, market makers can directionally operate on prices, finally earning money from price movements rather than just spreads as service fees.

2. Introduction to Classic Signals

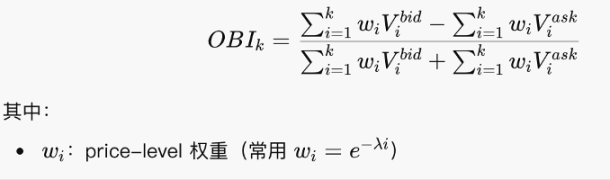

2.1 Order Book Imbalance: OBI

OBI looks at which side has “more standing orders” near the current price level, serving as a standardized volume differential statistic.

This formula is actually simple—it’s just a summed ratio logic, checking whether buy or sell orders dominate. An OBI approaching 1 indicates mostly bid orders, with a thick lower side. Approaching -1 indicates a thick upper side. Approaching 0 suggests a relatively symmetric buy-sell balance.

It’s important to note that OBI is a “static snapshot.” While it’s a classic indicator, it’s not effective on its own and must be used alongside cancellation ratios, order book slopes, etc.

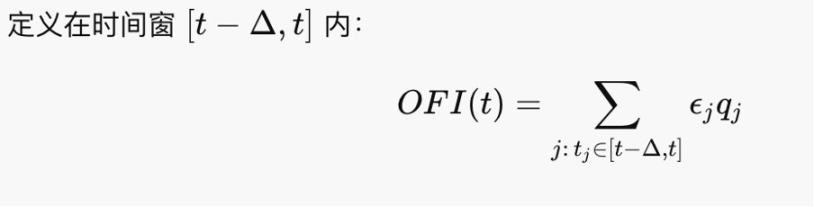

2.2 Order Flow Imbalance (OFI)

OFI looks at who is actively attacking over a recent short period. OFI is the first-order driver of price changes because prices are pushed by taker orders, not by resting orders.

It feels somewhat like net trading volume. In the Kyle (1985) framework, ΔP≈λ⋅OFI, where λ is tick depth, so OBI is the factor driving price movements.

2.3 Queue Dynamics

Most exchanges today follow continuous auction rules based on best price and first-come-first-served (FCFS) principles, so submitted orders queue up to be filled. The queue represents the resting order situation, which determines the order book state. Abnormal order book states (along with order replenishment and cancellation situations) hint at directional price changes, i.e., micro alpha.

Two scenarios to note in queues:

1. Iceberg: Hidden Orders

Example: Only 10 lots are shown on the surface, but each time they are filled, another 10 lots are immediately replenished. The actual intent might be 1,000 lots. The method I introduced in the first episode for annoying market makers to lower costs is essentially a manual iceberg. In practice, some players use iceberg orders to conceal their true order size.

2. Spoofing (Fake Orders)

Placing large orders on one side to create a “pressure illusion” and quickly canceling them before the price approaches. Spoofing contaminates OBI, slopes, etc., artificially thickening the queue and increasing movement risk. Additionally, large spoofs can intimidate the market and potentially manipulate prices. For instance, the London Stock Exchange reportedly caught someone manipulating forex in 2015 using spoofing. In the crypto world, we can also manually spoof to annoy market makers, but if the order is actually filled, your exposure becomes significant.

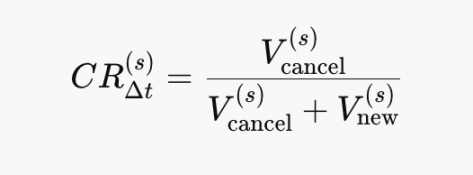

2.4 Order Book Cancellation Ratio (Cancel Ratio)

The cancellation ratio is an estimator of liquidity “disappearance rate”:

Cancellation↑⇒Slope↓⇒λ↑⇒ΔP becomes more sensitive. It is an instability signal that leads OFI. CR→1: Almost pure cancellations. CR→0: Almost pure replenishments. The mathematical formulas in this episode are simple and can be interpreted by looking at the diagrams.

CR↑⟹ Passive side perceives increased future risk. Also, CR is not used alone but alongside OFI and other indicators.

The above might just be a few outdated order book games, but market making evolves quickly. Moreover, with stocks moving on-chain, even traditional market makers might venture into on-chain market making. Still, these indicators remain useful and inspiring.

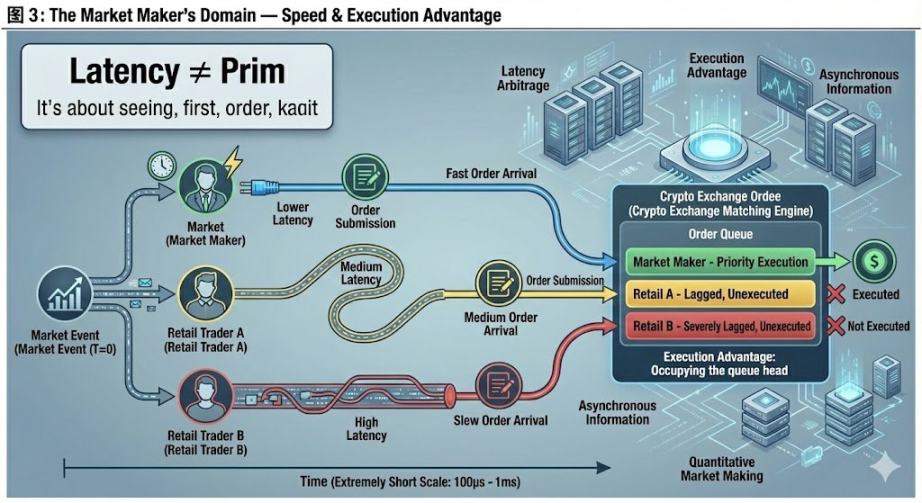

3. Market Maker’s Absolute Domain: Speed

In movies, we often hear about funds with faster internet speeds being more dominant. Many market makers even relocate their servers closer to exchange servers. Why is that? Finally, let’s discuss the advantages of physical equipment and the unique “execution advantages” in crypto exchanges.

Latency arbitrage is not about predicting future prices but executing buy/sell orders at more favorable prices before others “react.” In theoretical models: prices are continuous, and information is synchronized. But in reality: markets are event-driven, information arrives asynchronously. Why does information arrive asynchronously? Because receiving price signals from exchanges and sending order instructions to exchanges both take time—a limitation of the physical world. Even in fully compliant markets: different exchanges, data sources, matching engines, and geographical locations cause delays. Thus, market makers with more advanced equipment hold the initiative.

This tests the market maker’s own capabilities and has little to do with other players, so I consider it their absolute domain.

A simple example: Suppose you want to sell, quoting at the market’s best ask price. Theoretically, it should be filled. But I also want to sell, and because I see the price and quote faster than you, I fill the order first. Your inventory remains unsold, preventing your position from returning to neutral. Real situations are far more complex.

Interestingly, due to the lack of regulation, almost all crypto exchanges can grant specific accounts priority execution rights—essentially allowing them to cut in line. This is especially common in smaller exchanges, highlighting the importance of being an “insider” in crypto, comparable to research. Whether you can execute safely is a crucial step in transitioning alpha theory into practice.

This episode attempts to write from a market maker’s perspective. Actual operations are undoubtedly more complex—for example, dynamic queues involve many nuanced details in practice. Feedback from experts is welcome.

Postscript: One regret about this article is the title “Domain Expansion in Market Making.” I originally intended to discuss dynamic hedging and options, as I believe this is the conceptually most challenging aspect of market making, worthy of the “domain expansion”大招. However, after working on it for a day and writing half the article, I couldn’t figure out how to systematically explain it, so I switched to micro alpha. @agintender has an article covering many professional hedging concepts—encourage everyone to check it out.